In 2016, the ground up vs. rap bolting argument in rock climbing seems as dated as EB’s and painting knickers, but it could use some polish. Even here in North Carolina, where the ethic has remained with a strong traditional ground up backbone, the majority of route developers have embraced various ways to create a route. Each technique used to complete a first ascent has its pros and cons. Many misguided climbers don’t really care how a route was established and believe that each route should be equipped to their standard. This mindset also needs polishing. In areas with a traditional ground up backbone such as Looking Glass Rock, Whiteside, and Laurel Knob to name a few, the art form has remained strong, as it should. In other areas the tradition has more of a grey area and typically for good reason (soft rock, loose rock, lack of hooking placements, etc.) and other methods of route development have been embraced.

In line with the rest of the climbing world at the time, our region’s climbing pioneers stood firmly on clean climbing from the ground up. Bolts were placed minimally because they marred the rock and they were typically drilled by hand from hooks or stances. That ethic took patience and vision. Boldness was merely a product of the practice, but rarely was it the motivation. First ascents were hard earned, many involving several attempts and several down climbs before committing to unprotected moves or deciding to permanently change the rock and add a bolt. In a conversation last fall, Don Hunley recalled Jeep Gaskin’s several attempts to free climb The Odyssey at Looking Glass. As Hunley remembered it, seeing Gaskin climb up to cruxes, then back off, then back up several times before giving it a clean ‘go’ helped him prepare for physical and mental cruxes on the Odyssey and many of his other great routes throughout our region.

This slow process and hard earned strategy runs contrary to how the majority of people enjoy climbing in the new millennium. Most new age climbers want to be able to on-sight a route and/ or know that their potential fall is well protected. Many new age climbers feel that every route should have protection or bolts every body-length and every route should end with a two bolt anchor at 100 feet or less. Looking back at my “tick list”, I am no better. That said, I respect the routes that I will likely never have the mind or body to climb. Looking Glass Rock’s Legendary Nuclear Bomb is a good example. I love water groove climbing. They each have such different characteristics, varied and weird movement, and are typically the most aesthetic features on our region’s granite domes. The Legendary Nuclear Bomb is THE classic water groove of North Carolina, a beautiful black groove that ascends a 600 foot plumb line up the nearly vertical Sun Wall. It is rated 5.11bR and reportedly has several moves where a fall would result in hopping back to the car at the very least. Although I would love to climb it, I have never lead it and likely never will (but hey, I’ll follow you on it!). If it had known protection or bolts every body-length, I likely would have climbed it several times by now. That said, I much prefer the way the climb is now; less protected and surrounded by more mystique due to its psychological nature. A lead on this route is hard earned, nearly as hard earned as the first ascent years back. The leader must be ready for, and train for, several cruxes both physical and psychological. The term “boldness” in climbing should be replaced here with “mental preparedness”. I know I am not mentally prepared to climb the Legendary Nuclear Bomb but in no way would I ever desire that someone add a bolt here and there to lower the high standard of mental preparedness needed to ascend the route. That would be akin to screwing an artificial hold onto a sport climb. For example, I will likely never be able to physically climb Hidden Valley’s best bolted roof route named Godzilla, 5.13a. I am completely mentally prepared to climb the route; falls are clean. My lack of physical preparedness does not make me want to add artificial holds to Godzilla, just like my lack of mental preparedness does not make me want to add a bolt to Legendary Nuclear Bomb. Both acts would degrade the character of the routes and would degrade the hard earned efforts of the route’s architects.

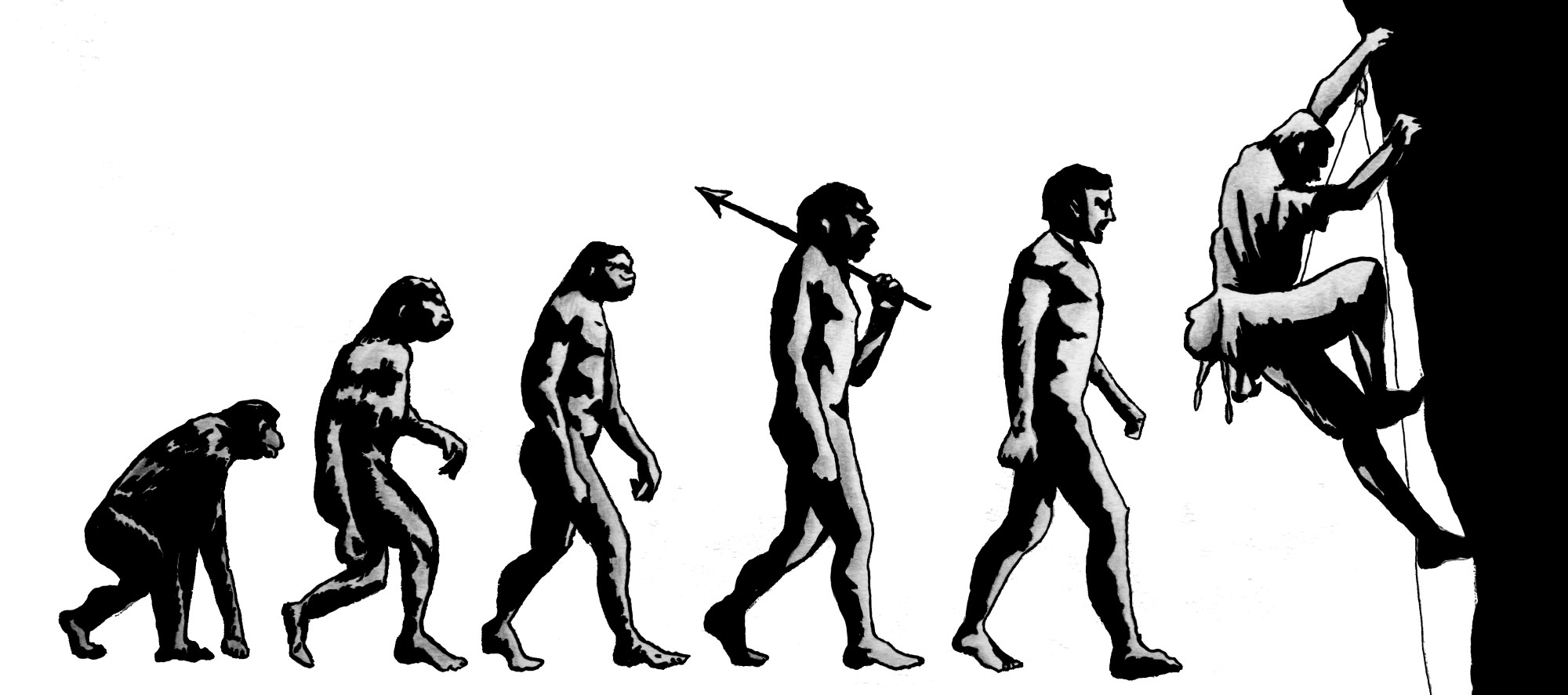

The sense of both discovery and creativity is hallmark to all human endeavors and for many, an innate desire. Discovering, uncovering, or establishing a previously unclimbed route or climbing area is no different. When establishing a new climbing route, a first ascensionist has an untold number of decisions to make based on rock type, local ethics, accessibility, and overall intention of the route. As with all creative processes, there is not a single “correct” way to go about it. As with all creative processes, authenticity should be the goal. Personally, I prefer ground up first ascents because they highlight the aforementioned sense of discovery, and I believe they leave a finished product for others to use that is more genuine with on-sight climbing. That said, I do not dogmatically hold onto any style and prefer to employee the style that makes the most sense based on the history of surrounding routes and based on rock type. Ground up ascents involve no prior inspection of the route. In a ground up ascent, the leader must drill a bolt from a good clipping or hook stance, meaning it will likely be in the correct place for the next person clipping that same piece. It is a lot of work to put in a bolt on lead, so bolting is naturally used only where needed. If there is a run out on the climb, it means that the first ascensionist went through that same run out without knowing what was to come ahead, as will the next climber attempting the on-sight. Ground up first ascents tend to take the most logical path of least resistance, which admittedly can be either a pro or a con. There are downfalls to ground up climbing. Without prior inspection of a route, it is easy to botch the intended route or underestimate its difficulty, causing unwanted aiding. It is possible that bolts drilled from stances could be placed with uneven holes, causing the bolt hanger to spin.

Rap bolting, the antithesis of ground up climbing, certainly has its pros and cons. There are benefits to dropping into a potential new line on a rope from above, working out the moves on a top rope, cleaning loose rock or lichen, and figuring out each exact bolt placement and clipping stance. Rap bolting generally involves more engineering and planning and can make a better protected line in the end, if that is the intent. Glue-in bolts can be used on top down ascents and have a longer shelf life, but these are typically not necessary in our granite. A rap bolted first ascent can be as genuinely conceived as a ground up first ascent, but the technique certainly has its cons. You can often tell when a climb has been rap bolted poorly when the bolts are nowhere near obvious stances or holds and the bolt is at your knees after you pulled a move. In rap bolting, it is difficult to judge what an on-sight climber would need as far as pro when you have already worked the moves via top rope. For example, several “bold” first ascents were first head-pointed several times on top rope before attempted as a “bold” lead. I disagree with this technique. If the moves have been rehearsed, the climb should be created in a way that reflects an on sight climb. Often with rap bolting, since the person knows what is coming ahead whether it be a jug or a gear placement, they will forego placing a bolt whether intended or not, because they know what is to come. The next on-sight climber will not know what is to come and since the route was manufactured in a top down fashion, the next on-sight climber has been duped in a potentially dangerous way. In summary, if rap bolting, make it safe as it is more authentic to what you, the first ascensionist are experiencing. In a ground up ascent, do what seems necessary or intended as it is your neck risked first and clean what you can. If the ascent occurred in a known climbing area, hopefully you have done your due diligence of checking to see if it was ever climbed before, then after the FA report to others on the seriousness or quality of the lead. If it is in an unknown area, either make it known or keep it quiet; that is obviously up to you as you did the work to find the place.

All of the above comments and techniques of new routing assume a lot of responsibility for the FA party. After all, the FA party’s friends or even children may climb a route they have developed. This brings to mind a misguided philosophy that some climbers have carried as more of a burden to themselves than anyone else; the expectation that every climb should be at their level. Nearly a decade ago, I sprained my ankle on a lead fall in Pisgah. I initially cursed the FA party of the climb, claiming that they should have placed another bolt. Years later, I now see why there is a run out, and I see my philosophical blunder. The route was certainly done ground up by the FA party and stopping mid sequence to drill would have been nearly impossible. The FA party could have finished the route, then lowered down and added a bolt but they didn’t, they left it in the original state and that is completely their decision. This is not selfish, rather it is more reflective of the original state of the climb and gives the climb its character. The crux of the route was a mental one, and the FA party decided to keep it that way. If the FA party decided to add a bolt there, that would have been their decision to make. That decision was earned by the FA party because they put in the time, effort, planning, research, skills, and vision to develop the route. Thinking back on my misguided expectations, I should have either been thanking the FA party for the bolt that caught my fall or should have not taken the mental test that the FA party produced.

What I love about North Carolina climbing, its history and evolving culture, is that personality and authenticity run paramount to ego. You can learn a lot about this personality by seeing who developed what routes, when, and how. With the onset of battery powered drills, developers could have easily dropped in from the top of Looking Glass and bolted every conceivable line every body length for the entire 600 foot length. Thankfully, they did not. Not that I do not like bolts, trust me, I do, but this act at many of our gear friendly granite domes would have been short sighted. It would certainly have degraded the aesthetics of the cliffs, degraded the education needed for a climber, placed an unneeded burden of maintenance for future generations, squandered the efforts of our climbing pioneers, and would have increased the impact on the natural resource ten fold.

All of the above narrative circles through my mind when I have the privilege to find a new potential route. The hope and intention is to create something that is genuine for future generations of climbers to enjoy or avoid. Each active route developer that I know currently in the Carolinas seems to share that same sentiment.